TO DO THIS WEEK:

We had the formative review on Tuesday! Considering how I kind of fucked myself with time management I think it went very well actually! Main points of feedback:

Also had a group tutorial with Louise and Emma after. It was quite useful, but also I got asked what my plans were for after the MRes which made me want to explode mildly. Guys is it normal to be 23 years old and have absolutely zero ambitions in life? Anyway key points or whatevar:

The other main event of the week was attending the intro to PhD study talk. While I don't think I'd want to go straight into PhD (especially after the talk - it really made me realise that I should have more of an idea what I want to do with my life before I start thinking about what to do for a PhD) it's definitely an option for later in life. Maybe five years from now or something when I'm a bit more settled in my life and what I'm doing with it.

Other key points:

With the thesis draft due in next week, it's time to start getting serious about writing up my analysis and editing the draft! First step, cutting out all my familiarisation notes I don't need anymore:

At this stage in research, I have just begun thematic analysis of my case studies. I am currently in the “familiarisation” phase of analysis. This phase “involves reading and re-reading through text-based data items, repeatedly viewing visual data items, and if working with transcripts of audio data, also listening to the audio recordings” (Braun and Clarke, p.43). The main goal is “capturing your ideas about potential patterning of meaning, and questions you may have” (Ibid., p.47) before moving onto the coding stage. As such, any findings reported here represent initial ideas about potential patterns.

The six case studies represent a range of approaches to depicting asexuality and aromanticism. Some, such as Sex Education, explicitly refer to these identities by name, while others, such as Game of Thrones, do not, instead describing defining features of asexuality without naming it. Some present an ‘insider’ perspective, where the audience is encouraged to put themselves in the a-spec character’s point of view - for example, Heartstopper follows Isaac (Tobie Donovan)’s point of view as he discovers he is aromantic and asexual. Other shows have an ‘outsider’ perspective, where the audience are expected to identify with another character who doesn’t understand asexuality or aromanticism – for example, the asexual characters we see in House are minor characters, and we follow Dr Wilson (Robert Sean Leonard) and Dr House (Hugh Laurie)’s reactions to meeting these characters. These represent crucial differences in approach across the different programmes.

However, there are also several potential similarities or common patterns between these programmes. Perhaps the most consistent is the construction of a-spec identity as unusual or in some way “remarkable” – in the most literal sense, a character’s a-spec identity is always considered something worth remarking upon. House is an extreme case of this, as it treats asexuality as something inherently suspicious, and in the end reveals that the seemingly asexual characters in the episode were either lying or had an illness causing their asexuality that needs to be cured. Dr House is proved correct in his belief that anyone who doesn’t want sex is either “sick, dead, or lying” (House, Better Half, 2012). However, even programmes that present asexuality/aromanticism as legitimate orientations still portray these experiences as unusual in some way. This can be expressed through a-spec characters being depicted as feeling isolated or unlike everyone else, such as in Sex Education or Heartstopper, or through other characters reacting in surprise to the idea of someone not experiencing attraction, such as in Game of Thrones (Game of Thrones, The Laws of Gods and Men, 2014). As such, it can be argued that a-spec identities were not fully normalised in any of the shows, they were always presented as a departure from the default in some respect.

Perhaps related to this, the general assumption seems to be that the audience will not be familiar with asexuality and aromanticism as concepts, so most programmes that use the terms feature some kind of scene where definitions of the terms are given, and the concepts are explained. The one major exception to this is The Imperfects, where the term “ace” is used without explanation, assuming the audience will know what it means (The Imperfects, Sarkov’s Children, 2022). Heartbreak High also does not feature a scene that explicitly explains what asexuality is, however by the time the term “ace” is used in the show (Heartbreak High, The Grapes of Voss, 2024), it has already been established that the character Ca$h (Will McDonald) has no interest in sex (Ibid., The Sheriff, 2022), so this could be considered a more subtle way to introduce the concept to an audience. This illustrates an assumption that asexuality and aromanticism are relatively “niche” topics, and implies that perhaps they are still viewed as unusual by the writers of these programmes. Another relevant factor is that half of the sample fall into the “teen show” genre, and historically depictions of queer characters in teen shows have demonstrated influence from the “Reithian ‘public service broadcasting’ notion that television can serve as an educative tool to improve and inform its audiences” (Davis, 2004, p.134) – this notion could also be an influence on depictions of a-spec identities, and the informative tone that many of them take.

There are also some common themes among the programmes, including self-discovery, the importance of “finding the words” for an experience, and relationships. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the teen shows had the most in common with each other. Heartstopper, Heartbreak High, and Sex Education all depicted a-spec characters (Isaac, Ca$h, and Florence (Mirren Mack), respectively) who go through similar “self-discovery” storylines, that start with them feeling isolated and different to everyone else, and result in them gaining self-acceptance.

However, some of the details of these stories differ. Heartstopper is the only one of the three to depict a character who is aromantic as well as asexual. Heartbreak High on the other hand, differs from the other two in the sense that it puts less emphasis on the importance of learning the terminology of asexuality and aromanticism, and depicts Ca$h as learning to accept his difference from everyone else without necessarily needing the exact terminology for it. Sex Education also stands out from the others because while its initial asexual storyline in season 2 episode 4 is very similar to storylines in the other two shows, it later introduces a second asexual character, O (Thaddea Graham). O has a very different storyline where she already knows she is asexual and her arc is more about learning to be open with others without fearing being judged for being different. However, despite these differences in execution, the programmes still have a great deal in common with regards to their use of self-discovery narratives. As all three of these programmes are teen shows, this could once again be a consequence of genre, since the “taking-on of a new, specific identity” in a self-discovery narrative can easily fit into the typical ‘coming-of-age’ story (Davis, 2004, p.131).

Alongside self-discovery, the other potential common theme is that of relationships, and the place of asexuality within a romantic relationship. This theme can be seen in Heartbreak High’s ongoing storyline where Ca$h tries to make a relationship work with Darren (James Majoos), who is not asexual, and in the plot of the House episode Better Half, which revolves around a (seemingly) asexual married couple. It can be seen to a more subtle degree in the conversation between Florence and Jean (Gillian Anderson) in Sex Education, where Florence insists that despite having no interest in sex, she “still want[s] to fall in love” (Sex Education, Season 2 Episode 4, 2020). With a few exceptions, depicting asexual characters as either in or interested in romantic relationships appears to be the norm.

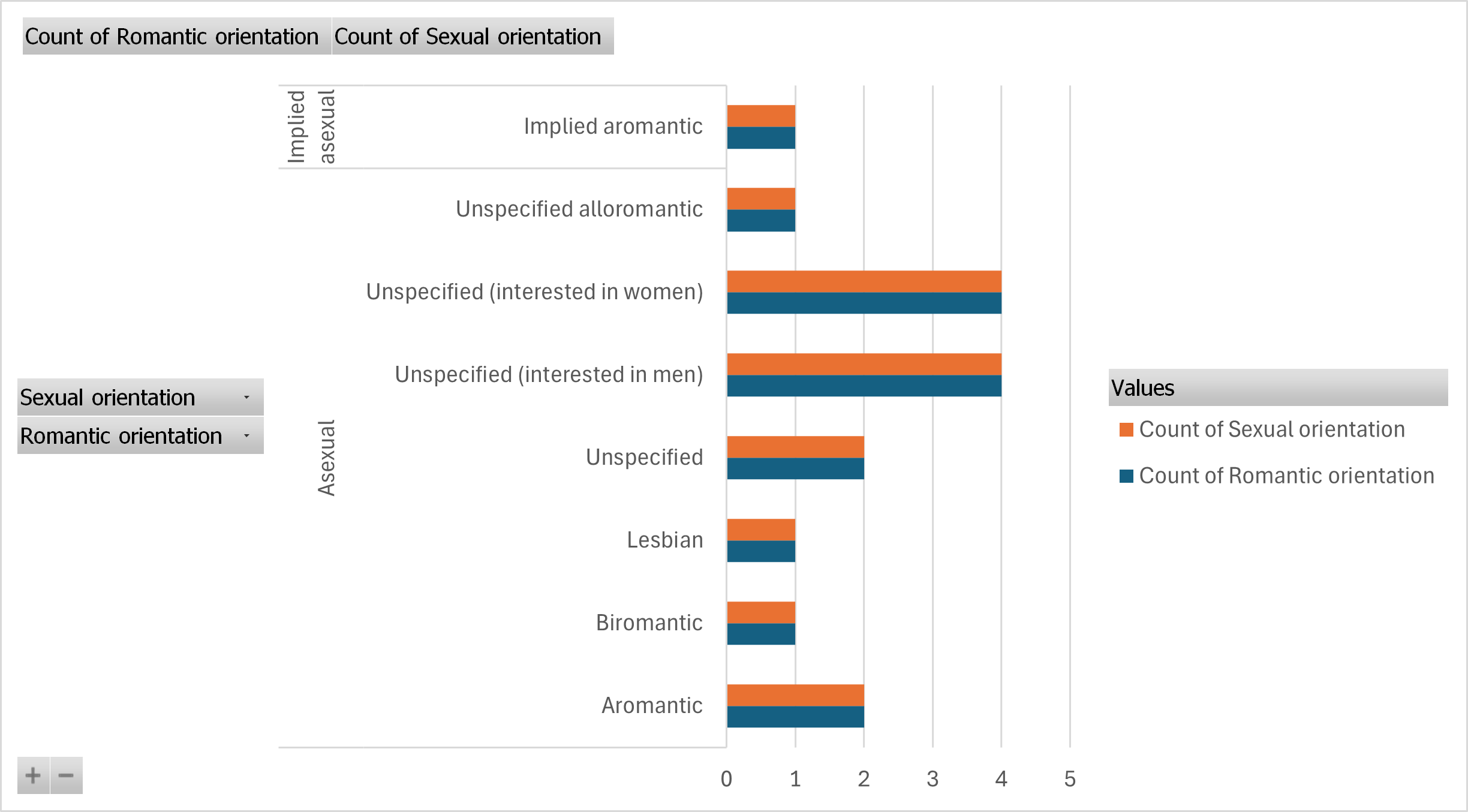

It is worth noting at this point that asexuality and aromanticism are generally treated very differently. While asexuality is usually explicitly present and defined, aromanticism is a lot murkier. Heartstopper is the only programme in the sample that uses the term “aromantic” (Heartstopper, Sorry, 2023), and many of the other programmes don’t even raise the possibility of a character not being interested in romance. Even when that possibility is raised, like in season 2 episode 4 of Sex Education, it is almost immediately established that the asexual character in question is not aromantic. Other times, it is left ambiguous if the asexual character is also aromantic or not, such as in Game of Thrones, or O in season 4 of Sex Education. Usually, a clear distinction will be made between asexuality and aromanticism, and as stated above asexual characters are often shown in relationships or at least interested in relationships. Overall, there appears to be more focus on asexuality than on aromanticism.

The prominence of romantic relationships can potentially be linked to the relative lack of portrayals of aromanticism. It is possible that this theme is common due to a wish to distinguish clearly between asexuality and aromanticism, or on the other hand it is possible that aromanticism is less well-represented because of the popularity of romantic arcs. Chen’s (2020, p.133) observation that aromanticism is viewed as “one step further from normal” feels pertinent here – perhaps in an effort to normalise asexuality by portraying asexual characters as still interested in romantic relationships, aromanticism has been left by the wayside. The prominence of the teen show genre could again be relevant, as the “‘frustrated romance’ narrative” is a generic staple (Bavidge, 2004, p.50). Whatever the reason, there certainly appears to be a reluctance in these programmes to address aromanticism.

Overall, the six case studies represent a wide range of different approaches to a-spec identity. However, despite the diversity of case studies, I have already identified some potential patterns. These include the construction of a-spec identity as “remarkable”, an assumption that the audience need to be educated, a focus on asexuality over aromanticism, and themes of self-discovery and romantic relationships.

In the next unit, thematic analysis will be developed further, and content analysis and focus group interviews will be carried out.

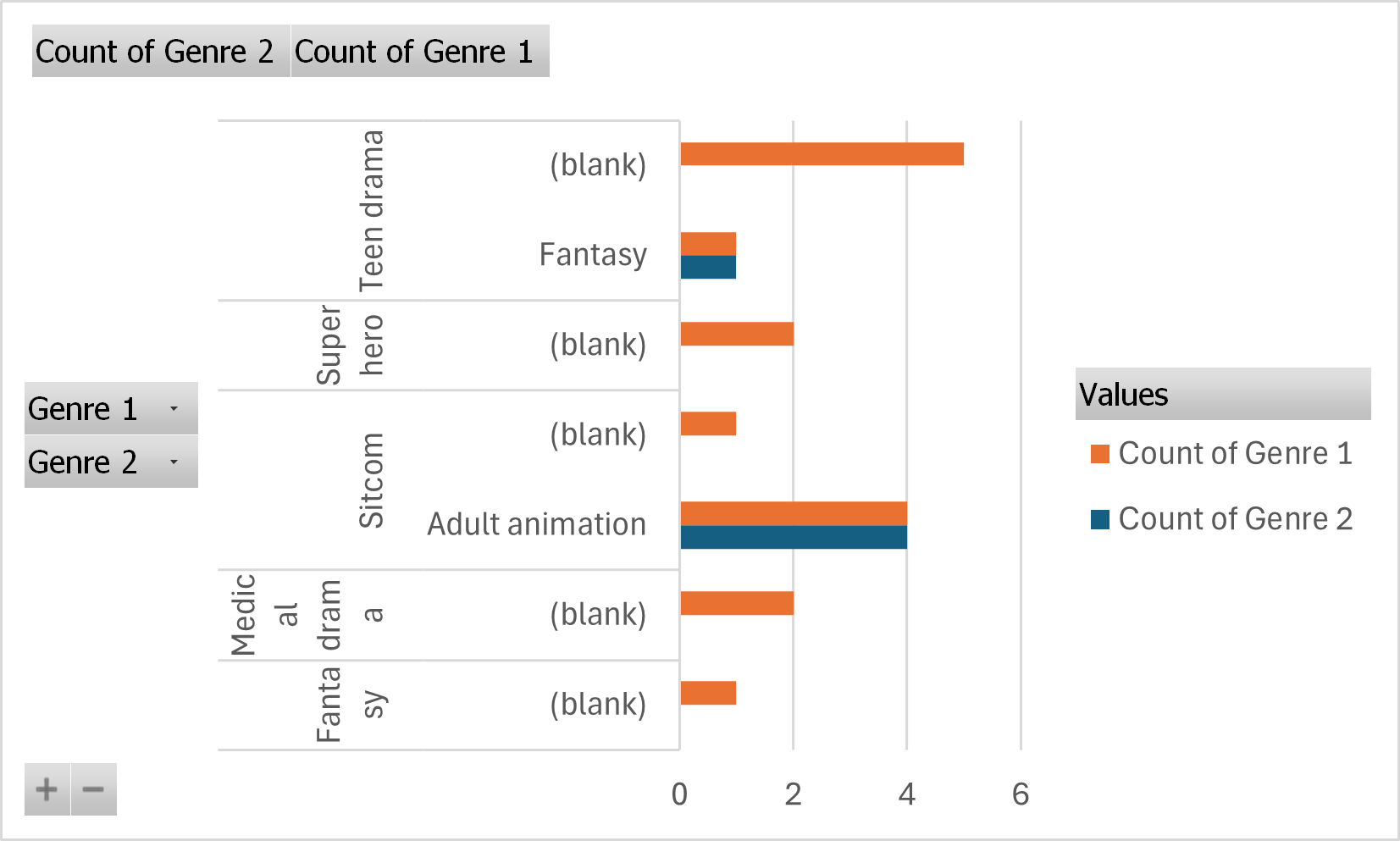

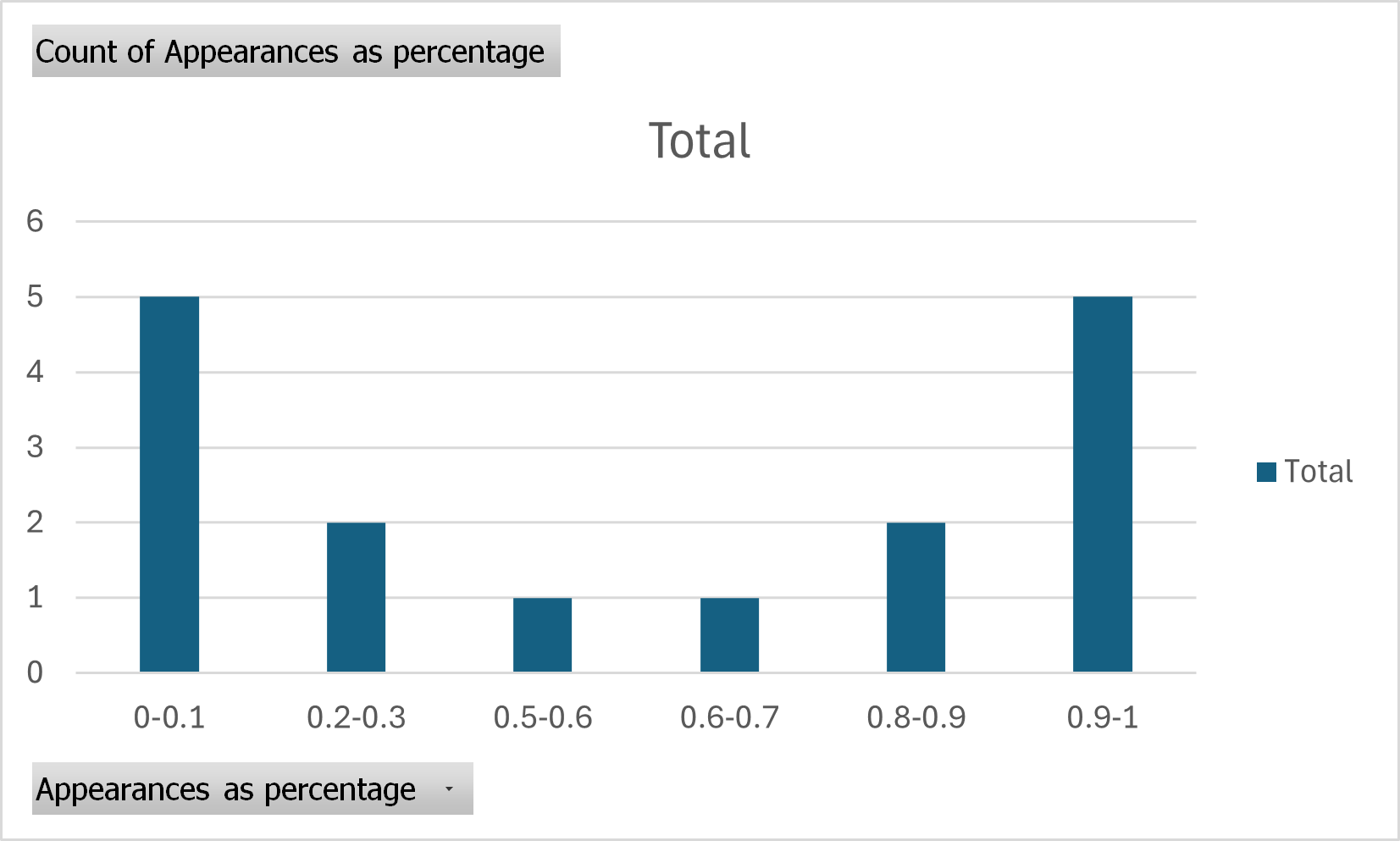

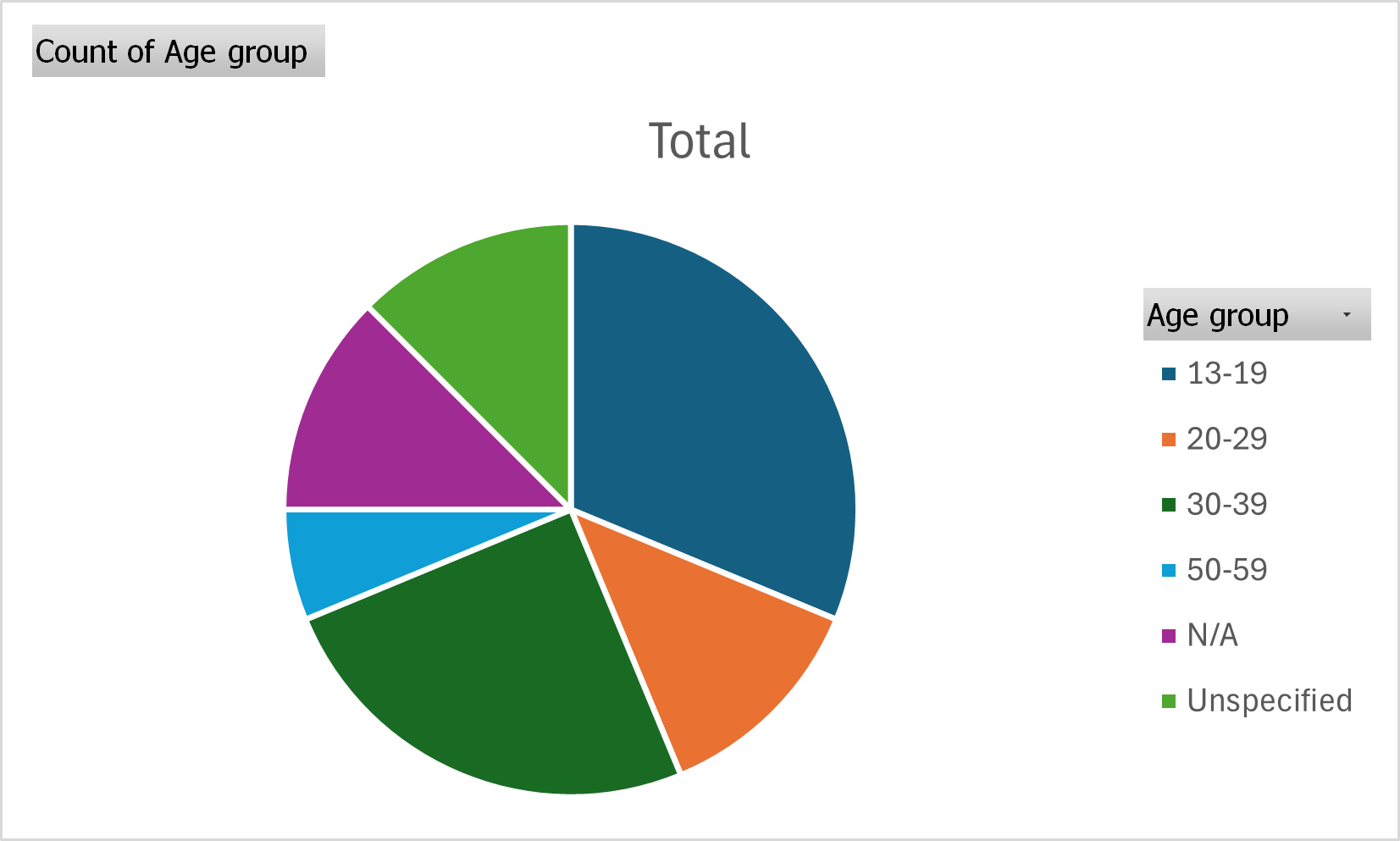

In addition to this thematic analysis of the chosen case studies, I will also be conducting a content analysis of a larger sample of TV shows. Content analysis measures “the frequency of appearance of particular elements in the text” in order to determine “the significance of particular ideas or meanings” (Jupp, 2006, p.40). Quantitative methods like this “usually generate large amounts of simple, numerical data” from a large number of texts (Davis, 2008, p.57). This will allow me to gain an understanding of the broader patterns evident in the full sample. Combining these two methods will allow for both depth and breadth in my analysis of TV portrayals of asexuality and aromanticism. - THIS IS ALL NO LONGER TRUE TEE HEE

The question of how media portrays certain social groups is fundamentally a question of ideology. Orlebar (2011, p.53) defines ideology as “the ‘natural’ and common-sense values that keep civil society running”.

The question of how ideology is produced in media is a matter of some controversy, not helped by the fact that studies of television “seldom […] pinpoint how specific content arises”, so much of the subject is left to speculation (Butsch, 2015, p.508). Feminist criticism of the media has been particularly concerned with where these messages come from. Different schools of feminist thought have reached different conclusions, with liberal feminism arguing that messages about gender in the media are simply the result of the media “reflect[ing] dominant social values” (Van Zoonen, [1991] 2012, p.27), which Tuchman ([1978] 2012, p.43) calls the “reflection hypothesis”

As discussed above, ideology is widely discussed in TV studies in regards to the issue of how specific groups are depicted, “sometimes stereotypically, sometimes narrowly, sometimes negatively” (Holland, 2017, p.60). However, broader issues of ideology are also relevant to TV studies

This thesis will explore how TV’s ideological role can be applied to societal attitudes towards a-spec identities, as well as attitudes around sex and relationships more generally. This thesis will take an approach based on the feminist “reflection hypothesis”, taking the stance that ideas presented in media are, generally, a reflection of dominant societal ideas and stereotypes. While some TV shows may challenge dominant ideas in at least some respects, these will be exceptions to the broader pattern. As such, the ideas presented in TV texts can provide us with insights into what constitute dominant ideas.

• A-spec is not default o Example – The Imperfects o Explanation – Explores how a-spec identity is depicted as unusual or non-normative. Can be more extreme, portraying it as an object of fascination, or can simply be expressed through a-spec characters having to announce their difference from the default o Link to societal attitudes – Demonstrates that even shows that aim to validate a-spec identity often do demonstrate elements of compulsory sexuality/amatonormativity (or maybe this merely accurately reflects the lived truth of the majority. We’ll see when we get to the focus groups…)

• It’s ok to be a-spec o Example – Heartbreak High s2e8 o Explanation – Idea of a-spec orientations being valid identities deserving of respect, quite didactic approach o Link to societal attitudes/wider context – Reithian model, similar to early queer depictions, rejects idea of a-spec as an impossibility or a problem but can still co-exist with idea of a-spec as a negative

• Sex is a big deal o Example – House, Heartbreak High s2e7 (sexuality as most important trait) o Explanation – Core idea about the importance of sex, at its most extreme can be seen in the idea that sex is a fundamental part of human nature/a human need, less extreme manifestation is the idea of sexuality being the most important part of someone’s identity o Link to societal attitudes – Foucault’s ideas about sexuality being constructed as the most important thing, also should probably bring up medicalisation stuff in regards to the House episode

• Sex is NOT a big deal o Example – Sex Education s2e4 o Explanation – Less prevalent but expresses the idea that sex isn’t as important as people make it out to be, both in relationships with others and also for individuals o Link to societal attitudes – Rejects compulsory sexuality (some might say… refusing compulsory sexuality…)